Venus used to have oceans, but a runaway greenhouse effect heated the planet up to 482 degrees Celsius (900 Fahrenheit) and they evaporated into space.

Friday, 29 November 2013

Wednesday, 27 November 2013

Beards and Staches and Sideburns, Oh My! The Luxuriant Science of Facial Hair

Each year men around the world take up their razors against

a sea of stubble to participate in what has become an incredible demonstration

of crowdsourcing and teamwork. These men grow mustaches and raise tens of

millions of dollars for prostate cancer research. The world has come to know

this event as Movember.

As noble a cause as Movember may seem, it does have one

unfortunate side effect. Try as they might, some “Mo Bros” will inevitably fall

short of their facial hair goals, even if their donations do not reflect this. As

a service to the follicley-challenged, we at Sketchy Science thought we would

attempt to explain why some men will end up looking more like Matthew Broderick

than Magnum P.I. come the end of the month.

Facial hair is a product of hormones and genetics.

Testosterone is the primary culprit in terms of facial, chest, and all other

body hair in both men and women. The level of testosterone in your body is

dependent on a number of things including biology, and environmental

factors. As we saw in our discussion of epigenetics, even the lives of your recent ancestors might impact your DNA and

subsequently alter your ability to grow a mo. Diet also plays a key role with

zinc and magnesium needed to get the testosterone manufacturing process started and cholesterol needed to produce the actual hormone. Foods like eggs, spinach, nuts, avocados, and

balsamic vinegar are all fine choices if your want to improve your follicle

fecundity. Others like broccoli, cauliflower, and cabbage will help by lowering

levels of counteracting hormones like estrogen.

Testosterone acts like a messenger from your body to your

hair follicles. In the simplest possible terms, testosterone antagonizes the

follicle and tells it to grow, grow, grow. It physically changes the “peach

fuzz” many of us are born with, making it thicker, coarser, and darker. From

there, you’re off to the races.

Unfortunately, you may be stuck in the gate if your genetics

don’t cooperate. Studies have revealed that Testosterone isn’t the sole factor involved

in facial hair growth. Research involving Japanese men (a group that is

generally less able to grow facial hair) has shown that even men with little to

no visible facial hair can have levels of testosterone equal to or in excess of

their bearded brethren. The explanation lies in a person’s genetics.

Testosterone can yell at your hair follicles to grow until it’s throat is sore

but if your DNA doesn’t allow you to respond, you will remain baby-faced.

Genetics help determine what is called your testosterone sensitivity. High

testosterone sensitivity is not without its drawbacks, however. It has been

linked to male pattern baldness in addition to facial hair growth, possibly

explaining why Bruce Willis is considered a manly action-hero.

Recent research has also shown that, beyond being a good

tool for fundraising, a certain amount of facial hair might also help you

attract a mate (at least if you’re Caucasian). A team of Australian biologists

evaluated ratings of attractiveness and masculinity for men with no facial

hair, light stubble, heavy stubble, and full beards. Results indicated that

heavy stubble was the most attractive condition, with full beard, light

stubble, and clean shaven being less attractive. Men with full beards were

rated highest in terms of masculinity. The researchers suggest that facial hair

might serve as a signal regarding reproductive health and the ability of a man

to protect his family. It needs to be noted, however that all the men being

evaluated were of European descent as well has 80% of the women who did the

evaluating. Attractiveness ratings were also impacted by the stage of the woman evaluator's reproductive cycle, supporting the evolutionary explanation

offered by the researchers.

Whether or not you can grow a beard Karl Marx would be

jealous of, Movember represents a great cause. It is important to remember that

the quality of one’s facial hair is far less important than the quality of

one’s intentions. Cancer research is a good and noble thing and we at Sketchy

Science wish all Mo Bros and Mo Sistas good luck in their fundraising as we

close in on the end of this happily hairy month.

If you want to donate to this worth-while cause you can give through the mo spaces of:

The Writer: http://ca.movember.com/mospace/782322

The Illustrator: http://ca.movember.com/mospace/2300458

Their Team: http://ca.movember.com/team/992625

Friday, 22 November 2013

Sketchy Fact #16: Let Your Backbone Slide

The Hero shrew and the Thor Shrew are the only two known animals with interlocking vertebrae. Their backs are reportedly strong enough to support the weight of a fully grown man. That would be like a person piggybacking a blue whale.

Wednesday, 20 November 2013

Chinooks: The Good, the Bad, and the Windy

There are a lot of different ways in which weather can ruin

your day. You can suffer through ridiculous heat waves, frigid cold,

hurricanes, tornadoes, and hale the size of soft balls. The worst part about it

all is that predicting the specific behavior of weather patterns is difficult

verging on impossible. The last thing you want is to be surprised when you walk

out your front door… That is of course unless you live on the Eastern edge of

the Rocky Mountains in North America.

The weather on the leeward side of the continental divide is

variable to say the least. In Canada, residents of Alberta can vouch for the

fact that summers are short and mild while winter can go on for decades and

flash freeze the hair on your head. Indeed, the people of the prairie come from

a hardy stock. Occasionally, though some of them get to cheat their way out of

winter for a few days at a time.

Chinooks (also known as foehn winds) are a Calgarian’s best

friend. Over the course of a few hours, these warm winds can rush in from the

mountains and lift the temperature from sub-zero to nearly tropical. Examples of potent Chinooks seem to break all

the rules of Canadian winter. During the winter of 1962 the town of Pincher Creek, Alberta was greeted by a Chinook that caused the mercury to rise by an

astounding 41°C (74°F) in one hour resulting in a day-time

low of -19°C and a high of 22 (-2 to 72°F). In February 1992, Claresholm, Alberta

experienced a high of 24°C (75°F), one of the highest February temperatures

ever recorded in Canada. These Chinooks are certainly impressive, but

bragging rights in the warm winter wind department go to the town of Loma,

Montana where on January 15, 1972 the temperature fluctuated by 58°C (103°F)

from a low of -48 to a high of 9°C (-54 to 49°F).

For those of us who live beyond the reach of Chinooks, this

is all clearly unfair. Obviously the people in Alberta and Montana and the

handful of other places along the continent’s spine that experience nature’s

equivalent of a “Get Out of Jail, Free” card have made some deal with Satan.

Alas no, the science behind Chinooks is relatively straightforward.

As warm, moist air from the Pacific rushes up the western

edge of the Rockies, temperatures fall and water is dropped off in the form of

snow. The remaining dry, cold air crests the mountains and (in the manner of

cooled gases) begins to rapidly fall down the leeward side. As the air falls it

gets crunched together (becomes denser) and the temperature rises dramatically.

It is the same thing that happens in a piston when air compressed so rapidly

that it heats up to the point of exploding, only far more agreeable for people

who get in the way.

Rapidly condensing air does have its side effects, it must

be said. Though it might not feel like it on the level of everyday experience,

wind is very heavy stuff. If you weighed

a column of air 1 meter (3.28 feet) in diameter that extended to the top of the

atmosphere you could come up with a figure of about 10 tons (22,000 lbs).

Consequently, as cold air plummets down the side of a mountain, it tends to

pick up speed. Chinooks can reach hurricane speeds. On November 19, 1962 a

Chinook blasted through Lethbridge, Alberta at a speed of 171 km/hr (106 mph).

Summer weather in January is a perk that is not taken

lightly in the great white north, but having your house blow away will put you

at a powerful disadvantage when the arctic air mass reasserts itself, as it

inevitably does. There may be a lot of give and take when it comes to Chinooks,

but a little heat in the dead of winter is a pretty cool thing.

Friday, 15 November 2013

Sketchy Fact #15: The Windiest Place... In the Wuhrld

Wednesday, 13 November 2013

The Neanderthal Within: The Science of Cousin-Lovin’

One of the most interesting facts in the study of human

evolution is that for a very long stretch of time (much longer than modern

humans have existed) there were multiple species of humans running around the

planet trying to make their way. We (Homo

sapiens sapiens) represent the only surviving species on the branch on the

tree of life known as Homo.

So what happened to the others? There are too many stories

to tell in such a short article but one stands out as being worth sharing. It

is the story of our closest cousins. A group with whom we shared the planet for

roughly 160,000 years before they vanished about 40,000 years ago. Today we

call them Neanderthals (Homo

neanderthalensis).

In the same way that people are often hard on their

relatives, modern culture has been tough on Neanderthals. We tend to think of

them as prototypical cave-people. Hunched over, heavy brows, probably carrying

a club, and dumb as a rock. The problem with the Fred Flinstone view is that

the evidence contradicts it pretty badly.

The more Neanderthal skeletons we look at and the more sites

we examine, the more scientists are realizing that Neanderthals were the equal

of their H. sapiens counterparts. In

a lot of ways, they even had us bested. First and foremost, they were

physically stronger.

They were slightly shorter than modern

humans with males reaching an average height of about 5 foot 6 inches and

females just a touch over 5 feet tall,

but their bone structure suggests that they were more heavily muscled and the

injuries they routinely survived imply that they were tough as nails.

That is pretty unsurprising. You would expect a species of

human that lived in Europe during an ice age to be pretty tough. The second

fundamental difference between our species hits a little closer to the modern

human ego. Neanderthals may have been smarter than us.

Not only did the average Neanderthal have a larger brain

than a modern human, they also left behind evidence of art and advanced tool

making abilities. Some scientists have even suggested that modern humans stoleideas from Neanderthals when it can to making spear points and the like.

Clearly something isn’t adding up here. If Neanderthals were

stronger, smarter, and more technologically advanced than us, why aren’t they

around today? There are a couple explanations. First, brain size isn’t

everything. Recent research has suggested that a greater portion of a

Neanderthal’s brain was devoted to processing vision and movement and less was

devoted to social networking compared to modern humans.

Second, when you factor in brain to body mass ratio, modern humans aren’t left

as far behind.

The difference in technology can be explained by necessity.

Modern humans evolved in conditions that were less demanding than Neanderthals.

While they were chasing mammoths through blizzards, we were running around in

the warm climes of Africa. We had a lot of the same problems to solve, but they

had more of them overall.

Eventually when humans showed up in Europe we managed to

overtake Neanderthals in terms of population. It may have been luck, or it may

have been ingenuity. What is incontestable is that we edged them out, but we

may have not wiped them out. Recent analysis of Neanderthal DNA and comparisons

with our own genetic code strongly suggest that once we had them outnumbered,

we began absorbing them through interbreeding.

That is one of the great things about science. Just when you

think you have things figured out, you get an M. Night Shyamalan twist that leaves you questioning your whole

perception of things. It becomes a lot harder to think of Neanderthals as

club-carrying knuckle-draggers when you find out that the DNA of your average

person of European descent is 2.5% Neanderthal.

It looks like the branches on the tree of life are bit more

tangled up than we originally thought.

Friday, 8 November 2013

Sketchy Fact #14: Papua New Gatsby

The native people of the Papua New Guinea Highlands were first contacted by modern civilization in 1933, eight years after The Great Gatsby was published.

Wednesday, 6 November 2013

Volcanoes: Flatulence of the Earth

If I had to take a

guess at what really got the whole idea of “science” going, and if that

motivator was some singular event, I think the safe money would be on a

volcanic eruption. I imagine some early human scratching his head and looking

on with an expression of dumbfounded awe as a pyroclastic flow swept past at

100 km/hour, simultaneously burying him in a heap of ash

and debris and cooking him at a temperature up to 700 degrees C.

Whether they are entombing cavemen, spewing

lava into the air, or simply dominating the horizon volcanoes are one of the

few things that both the average person and the most devoted nerd can agree are

just plain awesome.

Volcanoes come in three main varieties:

spreading centre volcanoes, subduction zone volcanoes, and intraplate

volcanoes. Each is the result of intense pressure deep within the Earth and the

mechanics of tectonic plates.

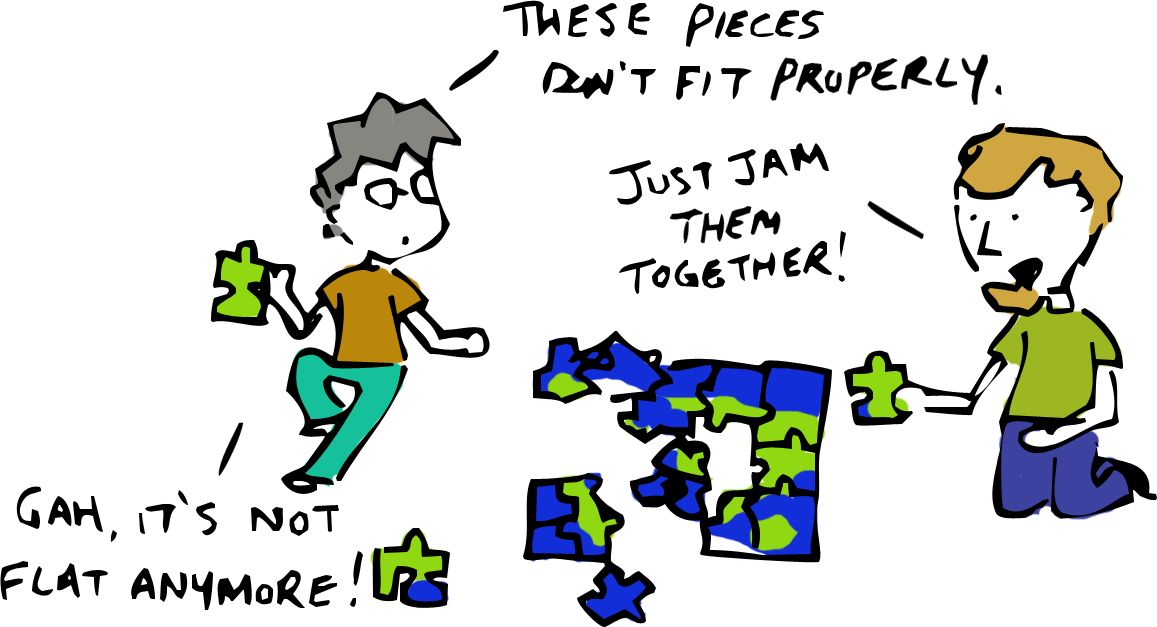

To really understand volcanoes you need to

understand plate tectonics. Since this article is meant to focus on the former,

I will sum up the latter in a single sentence: The Earth’s surface is made up

of enormous plates that fit together like a badly made jigsaw puzzle, moving

around and smashing into each other to produce all the features of the planet’s

landscapes.

When plates pull apart from one another,

hot rock from beneath bubbles to the surface and you get a spreading zone

volcano.

When two plates smash into each other, one is forced beneath the other

(AKA subduction) where the pressure and friction cause the rock to melt.

Eventually that rock finds its way up through cracks in the surrounding

material to the surface and you get a subduction zone volcano.

When you have a

plate with a weak spot and some particularly hot and motivated magma beneath

it, you get an intraplate volcano.

Beyond that, volcanoes don’t like it when

you try to come up with general rules about them. Spreading zone volcanoes tend

to be the least explosive, but Iceland is really just a combination of these

sorts of volcanoes and explosive eruptions there have halted global air traffic

and cost the world economy billions of dollars. Intraplate volcanoes tend to be the most destructive, but the Hawaiian hotspot

has been quietly erupting more or less constantly for at least the past

thousand years.

Clearly, volcanoes are full of surprises.

Unfortunately they are rarely the kind of surprises that you look forward to.

In 1980, volcanologists in Washington state watched and waited while Mount Saint Helens swelled and rumbled, expecting either an impressive vertical

eruption or for the volcano to slowly go back to sleep. No one predicted the

lateral (sideways) explosion of ash and debris that killed 57 people and

flattened 200 square miles of forest.

The most recent surprise that

volcanologists have unearthed is one that they seemingly should have discovered

quite a while ago. On September 6, 2013, scientists announced that they had

discovered the largest volcano on Earth (so far). Tamu Massif as the peak is

known rises 3.5 km from the sea floor about 1,600 kilometers east of Japan and

occupies an area of 310,000 square kilometers, making it about the size of the

British Isles.

The volcano formed over millions of years as eruptions piled up one on top of

another and collapsed outwards and upwards, although the summit still lies

about 2,000 meters (6500 feet) beneath the waves.

Tamu Massif is being compared to another

massive volcano called Olympus Mons which is found on Mars and still holds the

title of “biggest volcano in the solar system.” Until now, mountains as big as

Olympus Mons were not thought to exist on Earth. The reason is took so long to

find the behemoth volcano is that the world’s oceans are one of the few things

that are less well understood than volcanoes themselves. Also, scientists

originally thought the formation was the result of multiple volcanoes joining

together. The recent breakthrough was in establishing the existence of a single

vent responsible for forming Tamu.

It’s pretty incredible to think that

something like the world’s biggest volcano could exist beneath the ocean, unknown

to people, until the 21st century. It really makes you wonder what

other incredible things lay hidden by water and question whether or not it’s a

good idea to keep dumping radioactive waste and movie directors into the

depths.

Friday, 1 November 2013

Sketchy Fact #13: DNA in Spaaaaaaaaaaace!

If you stretched the DNA from a single cell into a fine thread it would be 2 meters (6.6 feet) long. All the DNA from all your cells arranged in a line would be twice the diameter of the solar system.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.png)